A good day

It's Sunday coming on sundown, and there are six men, one field over, behind three pair bulls, tilling with hand-carved wooden plows. Further up in the hills they're doing the same thing without animals, using chaqitacllas, wooden foot plows, same as the Inkas did.

It feels good to watch them and noodle on the guitar, it has been a tough few days. They are working their fields on a Sunday but I don't think they take that amiss.

They're about to plant maiz, what we call corn and natives call sara. It come in all colors and, in the hills, is grown without chemicals of any kind. Likely enough that field there. Monsanto will probably come by to sue them pretty soon.

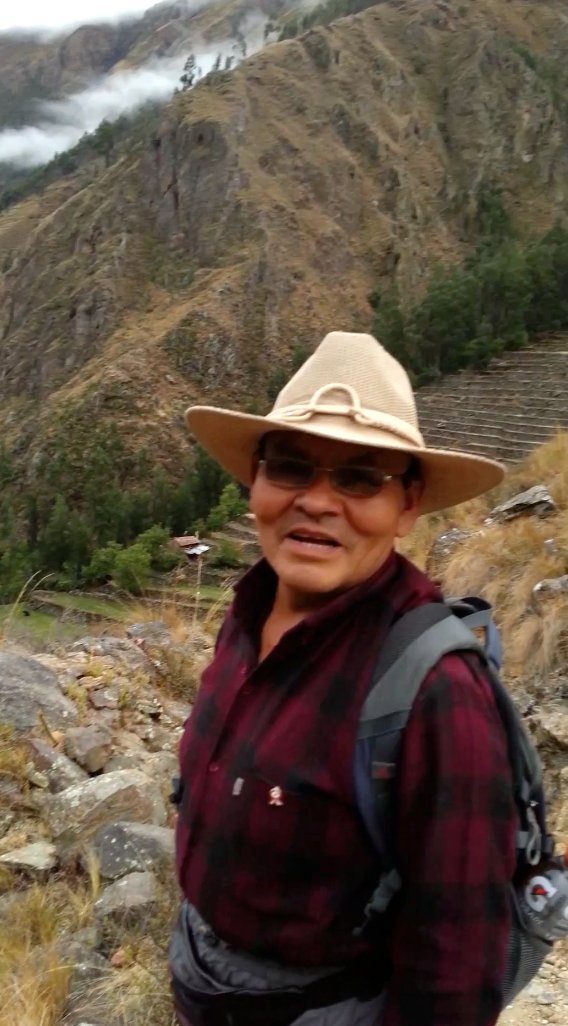

The field belongs to my landlady, Ricardina's, aunt. Yesterday her man, Ivan, also pure blood of the land, took me on a long hike on Bandolista mountain to the ruins at Pumamarka, a profound and mysterious pre-inca site. I'd heard of it, seen it on Googlemaps satview, but was amazed at its reality. I won't try to describe it. The web had nothing to offer but stub paragraphs and tourist reviews; I'd really like to debrief some Andeanist on that.

Afterward Ricardina met us at his Co-Mother's place back up the valley - he and she, the co-madre, are god parents to the same boy - ate trout and mixed veggies also from further back in the mountains in Huilloq, where the people dress to live in clothes I had thought were costumes for tourists. They don't give a fart about tourists, they farm for a living. And, well, sell some of those brilliant red ponchos to support their school.

We carried off a heavy sack of short, black, cobs of corn for Ricardina to cook to mush on an open fire in the back yard. They have cell phones and TV and the appurtenances of a modern kitchen but that's still how she renders her corn.

Okay. For a minute there I thought I wasn't going to make it here. It looked like the jaws of the beast called A Foreign Land were going to bite down on me. There was this interlinked crossfire of failures with my cell, internet, and banks - I couldn't call my banks because my cell wouldn't get international service, I couldn't communicate with the banks or the internet/cell carrier because my internet went dark, and both my debit cards went bad on me - one ate by the ATM, one refused my PIN. And I needed all of those to get my medical plan changed to work out-of-country. And it was cold dark and wet.

In Communist Avocado (out of contact) in a land where you don't speak the language worth a damn, and your money is all some thousands of miles away. Is how it felt.

Took a few days but it looks like that's all worked out. Shows you how prey you are to circumstance though, as an expat. Your support system is more vulnerable. I thought I might have to bail, and there are a lot of things yet to do and places yet to go. Anyway, I like this town. A lot.

It's Sunday coming on sundown, and there are six men, one field over, behind three pair bulls, tilling with hand-carved wooden plows. Further up in the hills they're doing the same thing without animals, using chaqitacllas, wooden foot plows, same as the Inkas did.

It feels good to watch them and noodle on the guitar, it has been a tough few days. They are working their fields on a Sunday but I don't think they take that amiss.

They're about to plant maiz, what we call corn and natives call sara. It come in all colors and, in the hills, is grown without chemicals of any kind. Likely enough that field there. Monsanto will probably come by to sue them pretty soon.

The field belongs to my landlady, Ricardina's, aunt. Yesterday her man, Ivan, also pure blood of the land, took me on a long hike on Bandolista mountain to the ruins at Pumamarka, a profound and mysterious pre-inca site. I'd heard of it, seen it on Googlemaps satview, but was amazed at its reality. I won't try to describe it. The web had nothing to offer but stub paragraphs and tourist reviews; I'd really like to debrief some Andeanist on that.

Afterward Ricardina met us at his Co-Mother's place back up the valley - he and she, the co-madre, are god parents to the same boy - ate trout and mixed veggies also from further back in the mountains in Huilloq, where the people dress to live in clothes I had thought were costumes for tourists. They don't give a fart about tourists, they farm for a living. And, well, sell some of those brilliant red ponchos to support their school.

We carried off a heavy sack of short, black, cobs of corn for Ricardina to cook to mush on an open fire in the back yard. They have cell phones and TV and the appurtenances of a modern kitchen but that's still how she renders her corn.

Okay. For a minute there I thought I wasn't going to make it here. It looked like the jaws of the beast called A Foreign Land were going to bite down on me. There was this interlinked crossfire of failures with my cell, internet, and banks - I couldn't call my banks because my cell wouldn't get international service, I couldn't communicate with the banks or the internet/cell carrier because my internet went dark, and both my debit cards went bad on me - one ate by the ATM, one refused my PIN. And I needed all of those to get my medical plan changed to work out-of-country. And it was cold dark and wet.

In Communist Avocado (out of contact) in a land where you don't speak the language worth a damn, and your money is all some thousands of miles away. Is how it felt.

Took a few days but it looks like that's all worked out. Shows you how prey you are to circumstance though, as an expat. Your support system is more vulnerable. I thought I might have to bail, and there are a lot of things yet to do and places yet to go. Anyway, I like this town. A lot.